A federal judge has ruled that Citibank isn't entitled to the return of $500 million it sent to various creditors last August. Kludgey software and a poorly designed user interface contributed to the massive screwup.

Citibank was acting as an agent for Revlon, which owed hundreds of millions of dollars to various creditors. On August 11, Citibank was supposed to send out interest payments totaling $7.8 million to these creditors.

However, Revlon was in the process of refinancing its debt—paying off a few creditors while rolling the rest of its debt into a new loan. And this, combined with the confusing interface of financial software called Flexcube, led the bank to accidentally pay back the principal on the entire loan—most of which wasn't due until 2023.

Here's how Judge Jesse Furman describes the situation:

On Flexcube, the easiest (or perhaps only) way to execute the transaction—to pay the Angelo Gordon Lenders their share of the principal and interim interest owed as of August 11, 2020, and then to reconstitute the 2016 Term Loan with the remaining Lenders—was to enter it in the system as if paying off the loan in its entirety, thereby triggering accrued interest payments to all Lenders, but to direct the principal portion of the payment to a "wash account"—"an internal Citibank account... to help ensure that money does not leave the bank."

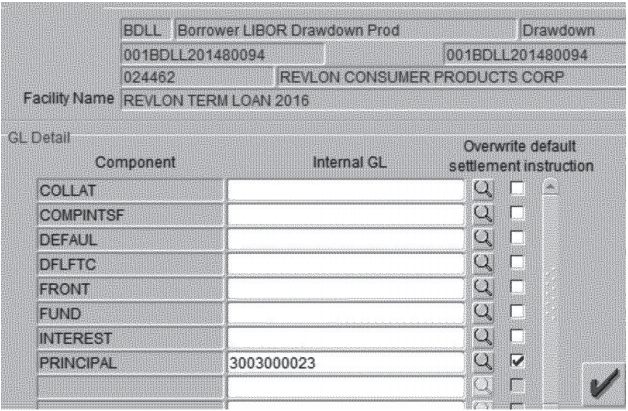

The actual work of entering this transaction into Flexcube fell to a subcontractor in India. He was presented with a Flexcube screen that looked like this:

The subcontractor thought that checking the "principal" checkbox and entering the number of a Citibank wash account would ensure that the principal payment would stay at Citibank. He was wrong. To prevent payment of the principal, the subcontractor actually needed to set the "front" and "fund" fields to the wash account as well as "principal." The subcontractor didn't do that.

Citibank's procedures require that three people sign off on a transaction of this size. In this case, that was the subcontractor, a colleague of his in India, and a senior Citibank official in Delaware. All three believed that setting the "principal" field to an internal wash account number would prevent payment of the principal. As he approved the transaction, the Delaware supervisor wrote: "looks good, please proceed. Principal is going to wash."

Revlon’s creditors were delighted

But the principal wasn't going to wash. When the subcontractor conducted a routine review the next morning, he noticed there was something drastically off about the previous day's figures. Citibank had actually sent out almost $900 million, not the $7.8 million it was trying to send.

Citibank then scrambled to get the funds back, notifying each creditor that the principal payments had been made by mistake. Some of the creditors sent the money back. But others refused, leaving Citibank out $500 million.

Ordinarily, paying back a loan early wouldn't be a big deal, since the parties could simply negotiate a new loan on similar terms. But in this case, some of the lenders were not on good terms with Revlon and Citibank.

Earlier in the year, as the pandemic was accelerating, Revlon experienced financial difficulties and sought to borrow more money. To do that, Revlon convinced a majority of its previous creditors to allow it to transfer collateral from its old loan to a new one.

The strong-arm tactic angered the other creditors, who felt that the reduced collateral could leave them holding the bag if Revlon ran out of money. That's more than a theoretical concern: Bloomberg's Matt Levine reports that Revlon's debt is "trading at around 42 cents on the dollar." But under the terms of the loan, the minority lenders didn't have a way to force early repayment.

So Citibank's screwup allowed Revlon's creditors to claw back cash that it might otherwise have never gotten back. And it could leave Revlon in a precarious financial situation if the company can't get the money back from the old lenders and can't find new lenders willing to replace the funds. Though given its screwup, Citibank could possibly end up as Revlon's new creditor.

The judge ruled against Citibank

Citibank sued, arguing that it was entitled to get the money back since the cash was sent out by mistake. Ordinarily, the law would be on Citibank's side here. Under New York law, someone who sends out an erroneous wire transfer—for example, sending a payment to the wrong account—is entitled to get the money back.

But the law makes an exception when a debtor accidentally wires money to a creditor. In that case, if the creditor doesn't have prior knowledge the payment was a mistake, it's free to treat it as a repayment of the loan. Judge Furman ruled that that principle applies here, even though Citibank notified its creditors of the mistake the very next day. The defendants noted that the amounts they received matched the amounts Revlon owed down to the penny, making it reasonable for them to assume it was an early repayment of the loan.

Furman also argued that it was reasonable for the creditors to assume that a bank as sophisticated as Citibank wouldn't send out such a large amount of money by accident.

"To believe that Citibank, one of the most sophisticated financial institutions in the world, had made a mistake that had never happened before, to the tune of nearly $1 billion—would have been borderline irrational," he wrote.

The case isn't over, however. Furman has ordered the creditors to keep the funds in escrow to give Citibank time to appeal his ruling.

"We strongly disagree with this decision and intend to appeal," Citibank said in a statement. "We believe we are entitled to the funds and will continue to pursue a complete recovery of them.

reader comments

313